Jamie Wilson reflects on service to US and Canadian Armed Forces

November 8 is known as Indigenous Veterans, Day.

Many Canadians recognize and honour November 11 every year to mark the armistice signed between nations at the end of World War I and the sacrifices that Canadians have made in armed conflict in the last century. It’s a solemn legacy that many Canadians regard with great pride and sorrow.

In 1994, Indigenous veterans advocated to be acknowledged after being excluded from recognition in Remembrance Day activities, despite the service they provided to Canada during wartime. Since then, November 8 has been observed as National Indigenous Veterans’ Day, a lesser-known observance to specifically recognize the contributions and sacrifices of Indigenous soldiers.

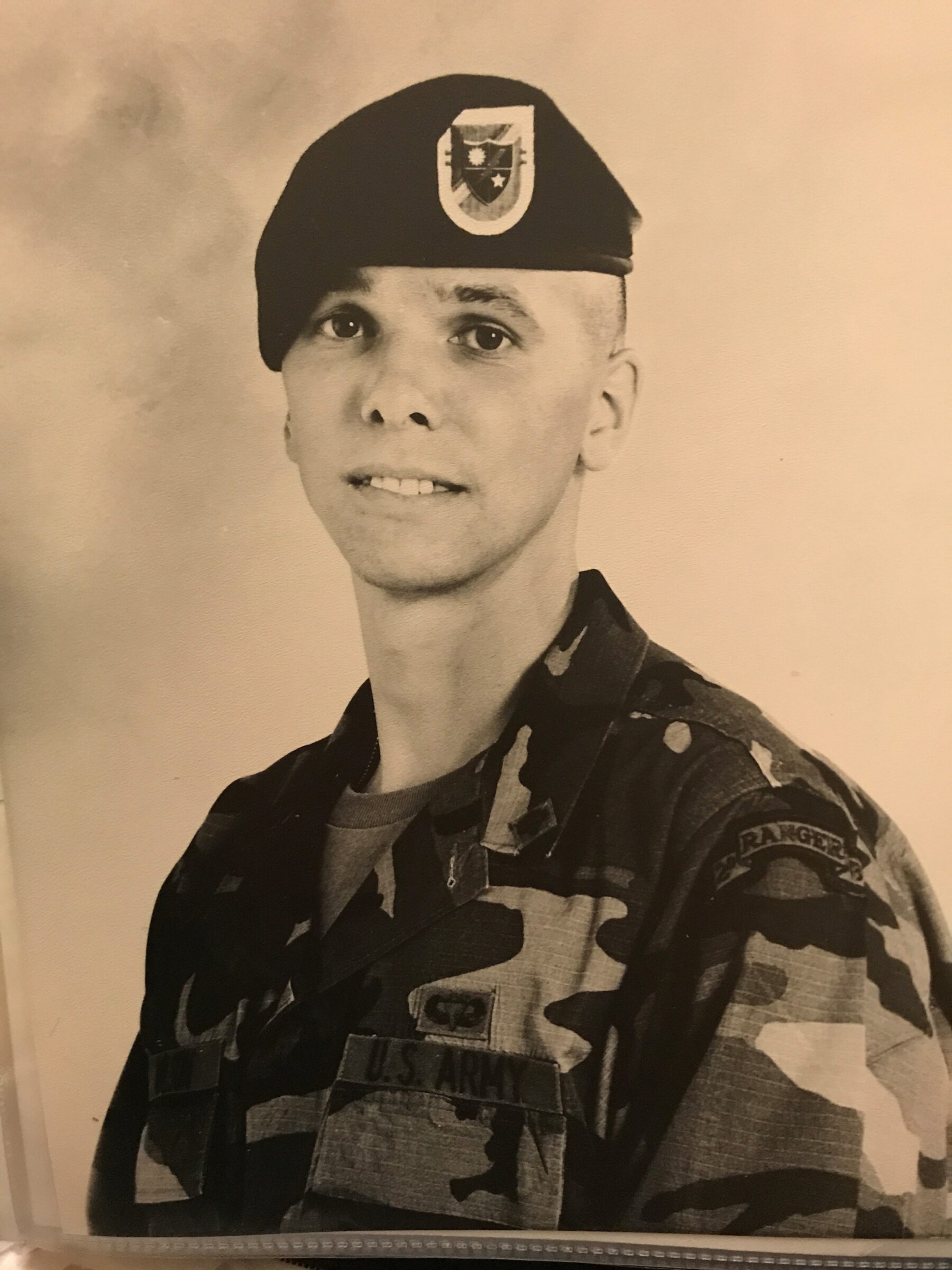

Before his career in education and post-secondary leadership, Jamie Wilson, Vice President, Indigenous Strategy, Research and Business Development at RRC Polytech spent nine years serving in both the US and Canadian Armed Forces – he says that his time in the military was the most formative time of his life and one that influenced his position as a leader today.

Wilson, who’s from Opaskwayak Cree Nation, grew up in a non-military family, but says his community has a proud history of serving during times of war.

“It’s an honourable thing to put your community ahead of yourself for the greater good. There are still young people back home that look to pursue military service—I’d support anyone that wanted to pursue it,” said Wilson.

Wilson had already earned his teaching credential in education when he began considering a career in the military.

In 1992, Wilson Sundanced in North Dakota with an Indigenous man whom he learned served in the US Special Operations—Wilson recalls being surprised that this laid-back, down-to-earth, traditional dancer willingly served in the US military while remaining true to who he was. Hearing about his fellow Sundancer’s experience reignited Jamie’s lifelong interest in joining the military.

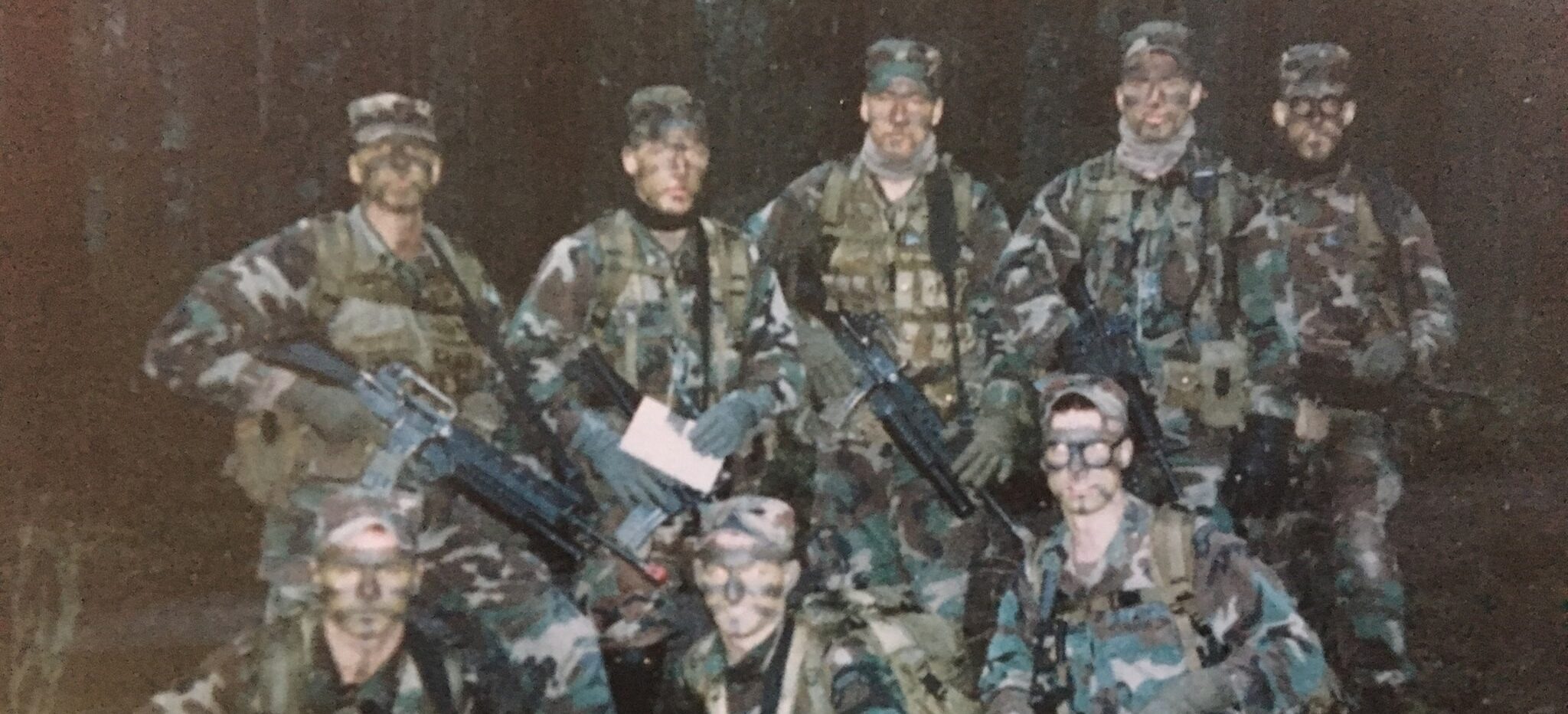

Under the Jay Treaty of 1794, Wilson, as a First Nations person, could travel and work in the United States with the same rights as a US citizen. Wilson spoke with a recruiter and joined the US army in 1994. He completed his basic training at Fort Benning, Georgia and was assigned a contract to attend selection with the 75th Ranger Regiment – a light infantry unit and special operations force within the United States Army Special Operations Command where he ended up spending two years serving. He says in that time, he experienced the toughest training conditions that forced him past his limits—limits he didn’t know could be exceeded.

“There were periods where we’d train constantly, for days straight—with a cumulative of 4-5 hours’ sleep the whole time. Going sometimes to the point of hallucination—some guys were walking and sleeping at the same time.”

Wilson noted that had he not Sundanced prior to joining the military, the experience would have been far more grueling.

“I used to do full Sundance for four full days—no eating or drinking water the whole time. I remember my military buddy, after the Sundance, was like ‘let’s run down to the [Missouri] river for the final ceremony; it’s only two miles away.’ We were dehydrated and hungry (I lost about 20 pounds in 4 days each time I danced), but I agreed—we ran there, and that made me realize the mental strength we have: you’re capable of more than you think.”

After returning to Canada, Wilson joined the Canadian Forces as a reserve infantry officer based in Edmonton for seven years. Looking back, Wilson acknowledged the hardship that soldiers go through to serve having experienced it firsthand in both the US and Canadian militaries, and the particular adversity that Indigenous soldiers and veterans have faced throughout history.

Wilson says that the leadership demonstrated in the military was more diverse than he expected—some of the best leaders he had were the ones that defied his expectations. Wilson says their abilities to serve as leaders were evidently forged from their abilities to support the people around them.

“It taught me to lean into myself more, to be more confident in who I am. It taught me to be a better parent, brother and leader. I learned to let myself make mistakes—they put you in uncomfortable situations to force you to grow and adapt. To be a good leader, you have to know how to be a good follower—you have to learn how to support those around you,” said Wilson.

For Wilson, National Indigenous Veterans Day and Remembrance Day is about recognizing the sacrifice of men and women who put their lives on the line.

“Whether it is serving overseas or local issues like flooding or fire, soldiers, sailors, airmen and women answer the call and exemplify selflessness by putting the greater good ahead of one’s self and personal needs every day to serve those around them.”

Many people express their support for National Indigenous Veterans Day by wearing beaded poppies created by Indigenous artists. Wilson encourages the community to show support by wearing a beaded poppy while also making a donation the Royal Canadian Legion, as every donation made for the yearly poppies goes toward programs that support veterans.

A History of Indigenous Veterans Serving In Canada

It wasn’t until 1994 Indigenous veterans and their families advocated for their recognition that Canadian society became conscious of the mistreatment that Indigenous soldiers faced when they returned home: Canada expropriated immense amounts of reserve lands during wartime, some of which was awarded as farmland to non-Indigenous veterans for their service; Indigenous veterans were often denied full veterans’ benefits and support programs afforded to non-Indigenous veterans; some were forced to “enfranchise” (meaning they became Canadian citizens with all the rights and privileges of citizens if they gave up their Indian Status and their identities).

Today, Indigenous people are recognized and honoured at all levels for their contributions to Canada during war. November 8th sees hundreds of ceremonies and vigils around the country to acknowledge the history that encompasses the Indigenous experience in the Canadian military.

Learn more about National Indigenous Veterans’ Day on the Library blog or check out these resources:

- Indigenous Veterans – Veterans Affairs Canada

- First Nations in Canada (rcaanc-cirnac.gc.ca)

- Civilization.ca – History of the Vote – Chronicle, A spotlight on 1920-1997 (historymuseum.ca)

- Why some Indigenous people chose to go to war for Canada | Folio (ualberta.ca)

- Indigenous Veterans Day Resource (trentu.ca)

- Support for Veterans (legion.ca)