Mino Bimaadiziwin – Living the Good Life at RRC Polytech

Mi – no Bi – MAH – di – zi – win: The Good Life

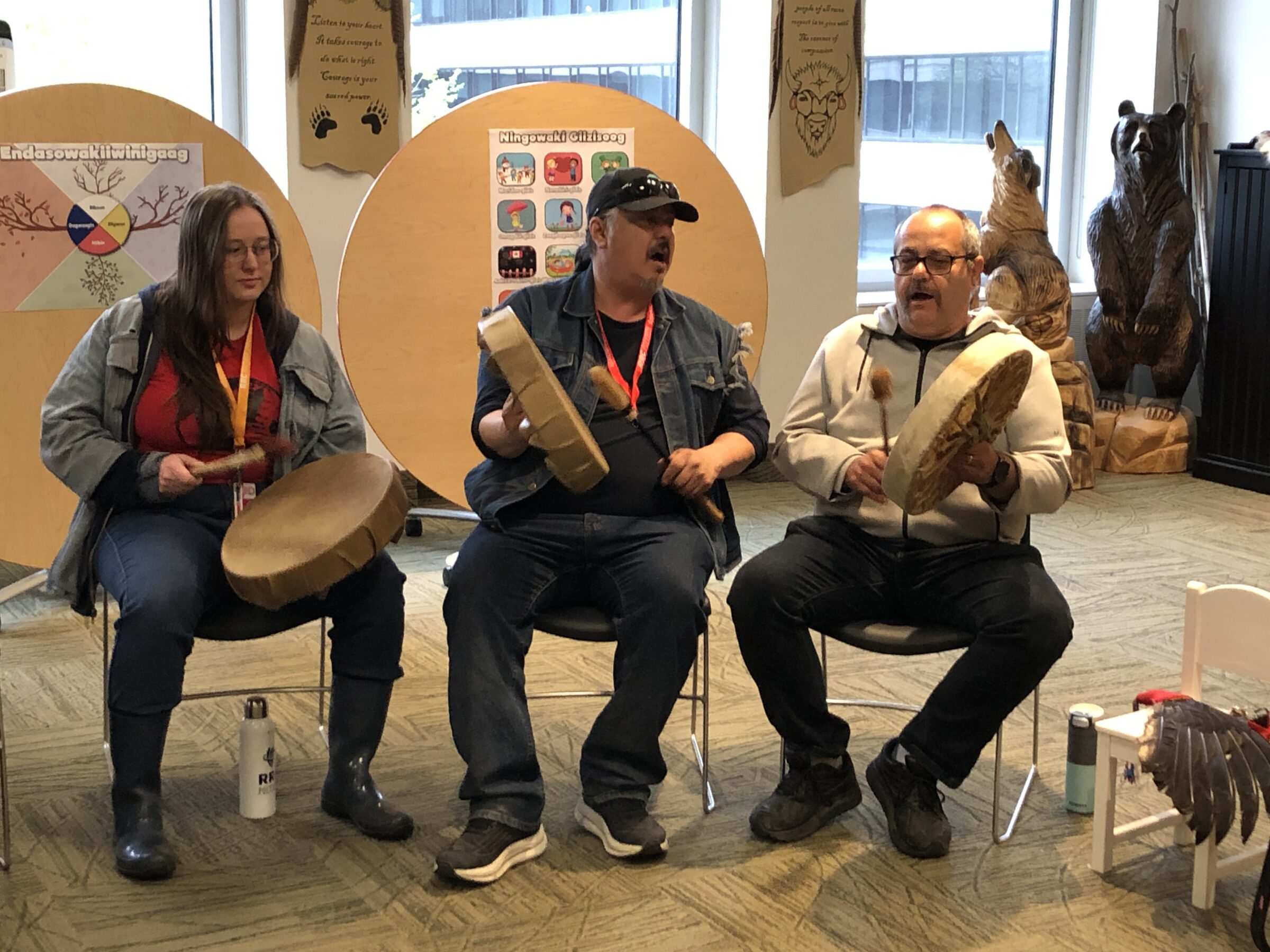

Over the course of three weeks in three-day blocks each week, staff and faculty at RRC Polytech had the opportunity to learn Anishinaabemowin and experience Anishinaabe ways of being with the guidance of gekinoo’amaaged, instructor, Corey Whitford of Sandy Bay First Nation and gichi-Anishinaabe, Elder, Paul Guimond of Sagkeeng First Nation.

Staff, now gikinoo’amawaaganag, or students, learned what it means to live authentically with the land, the seasons, and each other – what Anishinaabeg, the people, call Mino Bimaadiziwin, or the good life.

Whitford and Elder Guimond shared stories and memories, thoughts and feelings in a mix of Anishinaabemowin and English to expose students to the distinct cadences and inflections of either language. Much of Anishinaabe culture and history is rooted in the land, which Whitford heavily integrated into the course delivery – the pilot program was scheduled for early summer, so the Immersion Camp centred around the preparation for Sundance.

The first block comprised of storytelling and Teachings shared by Elder Guimond and Whitford to teach students about seasonal protocols associated with the six traditional Anishinaabe seasons and to associate Anishinaabemowin expressions with their meanings through experiential techniques, actions and gestures.

Whitford utilized the spaces at Notre Dame Campus to demonstrate that connection to space the language has – he guided students to the tiipii, or wigiyam, outside F Building and the Medicine Wheel Garden and the Sweat Lodge area, where Elder Guimond shared Teachings and histories about the traditional structures. Whitford outlined the next block deliveries in relation to the wigiyam and the Sweat Lodge, explaining how by the time the Immersion Camp came to a close, students will have helped prepare both a wigiyam and lodge for the Sundance in Sagkeeng First Nation in June.

“Corey taught us all the fundamentals of speaking, understanding the Anishinaabemowin alphabet and pronunciation, and the Teachings from Elder Paul about the wigiyam, the Buffalo Teachings, the Teachings about the Sweat Lodge, and Sundance Ceremony were incredible. The many sharing circles and discussions were community-building at its finest – we truly felt like family at the end of 9 days,” said Gerald Sereda, instructor.

Whitford coordinated several activities to relate the nature of Anishinaabe culture to participants – including the rope exercise, which he learned from an Inuk teacher. A thick rope is tied together at the ends to create a circle, which participants hold and lean back to create tension. A woman is lifted onto the rope, and walks around in a circle, touching the heads of the people holding the rope as she walks by. The exercise is meant to represent the strength that the community has, particularly men in the community, have and use and share to hold up the women in their lives.

Marie Rogge, instructor, says that the experience of walking the rope was spiritual and emotional.

“I was a bit speechless after stepping off the rope, but now wish I’d thanked the guys more and encouraged them to be strong for all the women in their lives – their grandmothers, mothers, wives or partners, daughters, friends, colleagues… Because we need each other to be all Creator meant us to be so partnerships, families, communities, colleges, businesses and nations can be strong and healthy,” said Rogge.

The second block took place in Sagkeeng First Nation where students engaged in land-based learning and walked through raising a wigiyam. Students went out on the land to harvest cedar and birch before stripping the trunks of their branches, leaves and bark to prepare as poles, then returned to the Sundance grounds to set up the wigiyam under Whitford’s guidance.

Students returned to Sagkeeng First Nation for the third and final block, where they washed and prepared buffalo skulls for Sundance while learning the significance of the practice with two women from Sagkeeng.

“Participating in the washing of the buffalo skulls in preparation for Sundance felt incredibly special. Using cedar water to wash the skulls was a powerful and spiritual experience, one that almost defies words. I am on my own grieving journey, and being able to participate in this ceremony was impactful and healing for me,” said Haley Pratt, Navigation Coach.

The Immersion Camp closed with a Sweat Lodge Ceremony in the lodge that students helped build with Elder Guimond and Whitford.

Jonah Schroeder, a recent graduate of Whitford’s Introduction to Anishinaabemowin class this past spring, says that learning the language has been indispensable in creating new friends and the Immersion Camp was the perfect opportunity to practice the language with new learners.

“It feels good to be in a community of fellow language learners, with great diversity in our life journeys and in our individual knowledge of Anishinaabemowin. We all support each other and have a special place in the circle we share,” said Schroeder.

He shared that during one of his walks through downtown Winnipeg, he passed through Central Park, where he says is a lively hub of kids playing soccer and friends sharing stories in an assortment of languages. An Anishinaabe man and his wife seated at a picnic table said something to Schroeder in Anishinaabemowin, not expecting him to respond – instead, Schroeder gave him a friendly greeting: “Boozhoo, boozhoo! Aaniin ezhi-ayaayeg?” Hello, hello! How are you two?

The three struck up a conversation in a mix of English and Anishinaabemowin, discussing their families, their homes and communities; why the couple were in Winnipeg, and why Schroeder was learning the language.

Schroeder says they must have chatted for twenty minutes before the new friends parted ways.

“I have been trying to learn Anishinaabemowin for a few years on my own, but it is in community where the language really comes alive. We need to hear the sounds and feel the words. It opens doors…or perhaps better yet, it builds relationships – it creates family. At least, this has been my experience over and over again, and this story is but one example,” said Schroeder.

“Together, we all learned to motivate our activities using our relationality techniques – we used our head to think; heart to feel; and hands to do the task-at-hand; to present each activity in an Anishinaabe lens,” said Whitford.

Glossary

| Word | Pronunciation | Translation |

| Anishinaabe | ah-nish-in-AH-bay | person |

| Anishinaabeg | ah-nish-in-AH-bek | people |

| Anishinaabemowin | ah-nish-in-AH-bay-mo-in | the language |

| Gekinoo’amaaged | geh-kin-OOH-(short pause)-ah-MAH-ged | teacher, or instructor |

| Gichi-Anishinaabe | gih-chih-ah-nish-in-AH-bay | old person, Elder |

| Gikinoo’amawaaganag | geh-kin-OOH-(short pause)-ah-MAH-WAH-gah-nawg | student |

| Mino Bimaadiziwin | mih-no bih-MAH-dih-zih-win | the Good Life |

| Wigiyam | wih-gi-yahm | tiipii |

| Aaniin ezhi-ayaayeg? | ah-neen ezh-ih-(short pause)-ay-YAH-yeg? | How are you? (plural/asking more than one person) |